Why China is dithering on a national property tax

Beijing goes quiet on property tax amid trade war with the U.S. and looming economic woes in 2019

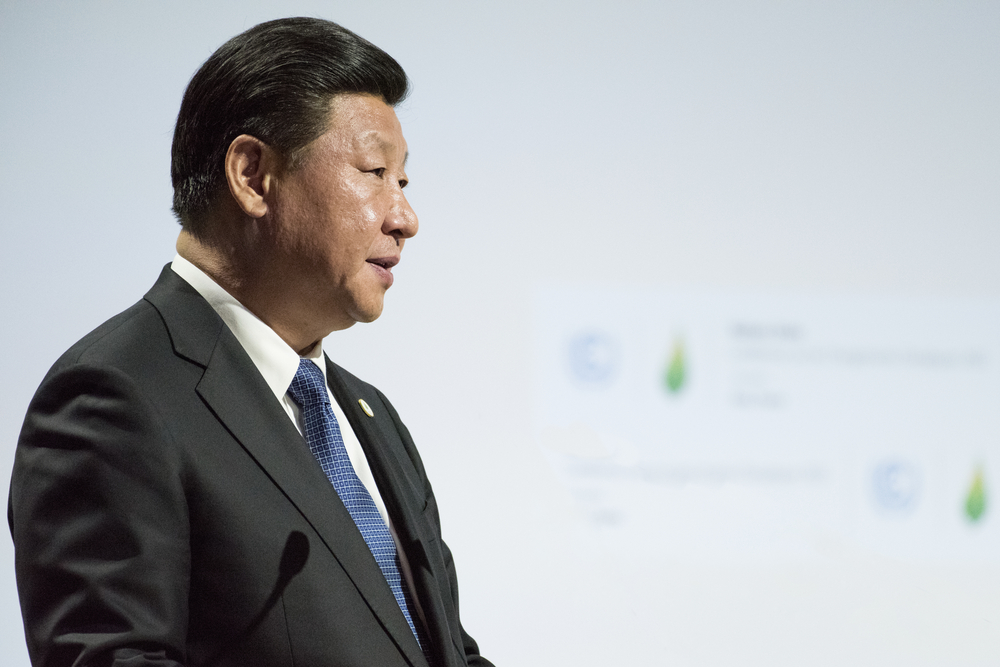

When China’s President Xi Jinping declared in October of 2017 that “houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation,” all bets were off: most seasoned China-watchers predicted it was only a matter of time before Beijing would enact a far-reaching property tax.

A series of related events further stoked the fire. That same month, then Finance Minister Xiao Jie said such tax would be based on appraisal values.

In June, the Chinese government completed a tool—a national real estate database—that would determine the value of every house in this country of 1.3 billion people. Whilst the government stated the database had nothing to do with plans for a new property tax, few accepted the explanation—even more so a month later when China’s Statistics Bureau announced that a property tax would be enacted at a faster pace.

Then, Chinese property stocks fell sharply over fears buyer appetite would contract, with part state-run Poly Real Estate Group—the fifth-largest developer in China with revenues of 146 billion yuan (USD212.5 million) last year—recording the sharpest drop as its shares slumped 3.3 percent in Shanghai.

More: Beijing’s battle for clean air

As the country’s top officials met in Beijing for key government meetings last September, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress announced a property tax among 69 priority levies over the next five years. It had been years since a property tax had been mentioned among the central government’s taxation timetable, suggesting that this time Beijing was serious. Local media covering the meetings quoted government officials appearing to sing from the same hymn sheet: a property tax was “crucial” for managing the world’s largest property market and would “definitely” be up for legislative review by the end of 2018.

Then though, silence, as problems have mounted for the world’s second-largest economy. The U.S.-China trade war beginning in July had kept on going, prompting downgrades on China’s economic forecast for 2019 and beyond. As soon as the New Year fireworks burned out in cities around the globe, stock markets tanked, with many analysts blaming China and its slowing economy.

The property market—particularly in China’s largest cities—has now all but stagnated. Whereas analysts interviewed by Reuters in September predicted 3.3 percent growth in Chinese residential sales during the first half of 2019, by January the same analysts slashed this forecast to two percent, sliding to a paltry 0.5 percent for the second half of 2019.

And just like that, a property tax appears all but forgotten.

The most important thing is how a new property tax can replace the practice where the local government is selling land. If you don’t allow them to sell land, how can they get their income out of the land?

David Tao, chief China economist at UBS Investment Bank, predicted a year ago the tax would be introduced by the end of 2019. By end 2018, Tao severely downgraded his forecast as China’s economic situation changed for the worse. “Previous property policy tightening has likely peaked, and a property tax will also likely be further delayed or muted,” says Tao, adding that Beijing may even ease property purchasing restrictions should the U.S.-China trade war drag on.

For the moment, Beijing looks set to focus on putting out economic fires as more existential issues—many borne of reforms Deng Xiaoping started in the late 1970s—remain on the backburner. It’s not the most desirable of outcomes as a tax on residential property lies at the very heart of China’s economic puzzle, notes David Ji, head of research on Greater China at Knight Frank’s Hong Kong office. Ji tells Property Report, “The most important thing is how a new property tax can replace the practice where the local government is selling land. If you don’t allow them to sell land, how can they get their income out of the land?”

In the absence of such a tax, local governments in China have sold land, mostly arable, to developers to fund local state spending. This in turn has changed the face of China’s geography and economy as cities have swallowed the countryside, with corrupt officials and developers becoming fabulously wealthy, driving the market for second and luxury homes.

As Beijing has enacted ever-elaborate restrictions on buying—different per city—this has consequently spurred rampant real-estate speculation and an over-dependence on the property sector, which creeps into every facet of China’s economy. China’s only major economic slowdown since Deng’s reforms—in 2015 and 2016—formed due to severe over construction, the ghost towns for which China has since become notorious.

Although the central government began experimenting with property taxes in Shanghai and Chongqing back in 2011, placing levies on second-home and out-of-town buyers, few tangible results materialized to instruct a nationwide tax, says Ji. “The clauses were too complicated, even for people in the industry,” he points out. “They don’t know who to tax to start with.”

Like Tao and other China watchers, Ji now believes a property tax has been delayed indefinitely. With Beijing looking to address more pressing economic concerns, the very fact the complex effects of the tax will likely seep into most corners of China’s enormously complex economy further informs its decision to delay.

Whether or not the Chinese government is ready to pass a property tax, however, Beijing has another exacerbating concern to contend with: increasing capital flight overseas.

“Wealth per adult in China has more than quadrupled over the past six years, yet they have a few options for investing that money. Domestic banks offer low interest rates on deposits. The stock market is immature and volatile. Alternative investment products have proven risky and even fraudulent,” says Carrie Law, CEO of Juwai.com, the largest online portal for overseas property buyers from China. “For many Chinese, international real estate looks like the most reliable and trustworthy asset class.”

This article originally appeared in Issue No. 152 of PropertyGuru Property Report Magazine

Recommended

Meet the vagabond architect behind India’s housing scene

Vinu Daniel is helping to shake up India’s home building setting

Where Asian real estate stands in a fragmented, warmer world

Asia’s real estate industry faces many and varied challenges as external factors continue to bite

6 sights to see in Singapore’s Marine Parade

Handily located Marine Parade has emerged as a vibrant investment choice in the Lion City

There’s a township dedicated to health and wellness in Malaysia

Property seekers have their health needs catered for at KL Wellness City