Proptech paves the way for green building adoption in developing countries

Through technology, emerging countries will be able to democratise green buildings and advance the adoption of green certifications

In my country, we have this popular Filipino slang word promdi, derived from the phrase “from the” which is short for someone who came “from the provinces”. I am what you would call a promdi and it used to be that being called one was a bit condescending, because it made you feel stereotyped as an unsophisticated person from the countryside. But over the years, its meaning has changed, probably because many people from the provinces have made their name in Philippine society.

I was born and raised in a charming town in the province of La Union, a four-hour drive north of the capital. La Union is popular for its beach towns and for a surfing town called San Juan. On the weekends, we would catch a ride on colourful jeepneys, which are like small buses, on the way to the beach for a swim. I grew up near a farm where sunshine and the smell of growing crops, animal dung, and cultivated soil were constant.

I’d say I had a very simple but happy childhood — one that some city folk would call unsophisticated. But you grow up hearing of a better life in Manila so like many promdis, I eventually made the decision to leave the small town to go to the big city in search of a better life. It seemed like a great idea at the time.

Finding sophistication in a traditional dwelling

Fast forward 10 years later, I am now a full-fledged urban professional, firmly rooted in the big city. I also just came back from Sydney last September, having completed my Master of Sustainable Built Environment degree from the University of New South Wales.

Upon arrival in Metro Manila, I was required to do a two-week home quarantine. My apartment is a 60 square metre, one-bedroom unit with two small windows on the 40th floor of a dense condominium development. Gazing out of the tiny openings, I was reminded of life back in the province where my family had once lived in a bahay kubo (nipa hut).

This type of house is common in farming villages in the provinces, and to people from the city, the nipa hut may look a bit backward. But I remember it was never hot inside the hut because it had sufficient openings for cross-ventilation, and it allowed abundant natural daylight. The roof also had a steep pitch, which separated us from the rising hot air and provided for a cooler interior. The house was elevated through stilts, which prevented floodwater from entering during typhoon season.

The materials used were sustainably sourced from locally available materials.

These included bamboo, sawali (bamboo mats), and anahaw (palm) — all climate-appropriate, breathable materials that need minimal processing, from raw material extraction all the way to construction.

My 14 days of isolation and reflection made me realise that we, promdis, may have figured out sustainable design through vernacular architecture long before the concept even became a fashionable one in big cities. But even in the provinces, we are seeing so much change.

A cause for concern

My post-graduate thesis dealt with green building certification in the context of developing countries. During my research trip to my home country, I got the opportunity to go out of the metro, where I witnessed uncontrolled urban sprawl, conversion of precious agricultural land to concrete and asphalt, and unsustainable architecture, totally devoid of place and context.

The pressure to decongest urban areas through decentralisation — a trend not only seen in the Philippines, but across Asia — has resulted in the creation of new growth corridors or next wave cities. However, decentralisation is much more nuanced than just identifying strategic growth areas where population is projected to spike.

And what’s worrying is that we’re still designing and constructing our buildings like business as usual. This locks in inefficiencies in the real estate landscape, leading to vicious cycles that are hard to break out of, especially for a country like the Philippines, experiencing double exposure through rapid urbanisation and climate change.

The climate crisis

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the World Bank Group recognise climate change as an acute threat to global development that increases instability and contributes to poverty, fragility, and migration.

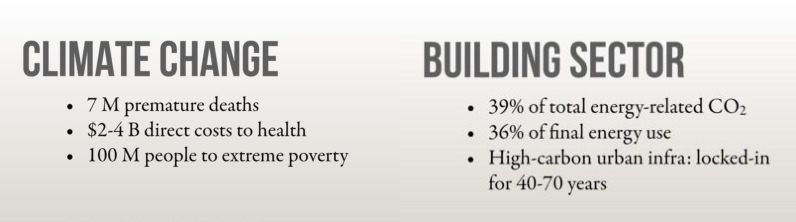

Co-pollutants associated with carbon emissions are already responsible for more than seven million premature deaths each year, while direct costs to health are estimated to be between USD2.4 billion per year by 2030. Climate change could force as many as 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030.

The building sector accounts for 39 percent of total energy related carbon dioxide emissions and 36 percent of final energy us. Without the right choices today, high carbon urban infrastructure will be locked in for the next 40 to 70 years.

The message from leading scientists at the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is that there is no time to waste. The world has just under a decade to avert climate catastrophe, with the IPCC recommending a 45 percent reduction in emissions below 2010 levels by 2030. The amount of coal in the global electricity mix would need to be reduced to close to zero percent by 2050. Green buildings have a major role to play.

Call to action: Global green building adoption

Since the Paris Agreement was signed in December 2015, there has been a strong demand from IFC clients in low- and middle-income countries for rapid, concerted action on climate change.

Green buildings are no longer just a trend. If we are to meet our Paris commitments, green buildings are an imperative. Towards this end, the IPCC has identified green building certification as an important pathway. And indeed, in the last decade, we’ve seen the rapid expansion of green building footprint.

According to data presented by the World Green Building Council, many developed countries already have a mature green building market. However, for countries in the Global South, the uptake of green buildings has been much slower. In the Philippines, for example, the current footprint of all green buildings combined is a mere 10 percent of what’s constructed annually. My country has almost 200 green buildings, but around 90 percent of these are commercial buildings dominated by office towers in the metro.

Green building opportunity in emerging countries

By 2060, the green building sector will double, occurring mostly in emerging markets, where a USD24.7 trillion investment opportunity in green buildings now exists.

According to IFC’s Green Buildings report, two thirds of this is in East Asia Pacific and South Asia, where more than four billion people are projected to live by 2030. In developed countries, the urban environment is mostly fully built up and retrofitting is a strategy towards increasing the footprint of green buildings. But in developing countries, building it right the first time seems to make more sense than building back better, as these countries are not fully built up yet.

Overcoming challenges through proptech in green buildings

Democratising green buildings is not as easy as it sounds. Developing countries face challenges that are very different from those encountered by developed countries. In Southeast Asia, some of the key issues are the higher real or perceived costs for building green, lack of trained or educated green building professionals, and the perception that green buildings are for high end projects only.

Through IFC’s Green Building Market Transformation Program, we are able to provide investment and advisory for banks and developers, as well as advise governments about green building codes and incentives.

In my role, I forge partnerships with real estate developers, investors, building professionals, certification providers, academia, and public policymakers across the country towards advancing the adoption of Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE).

EDGE is an integrated online platform, green building standard, and certification system, designed to make green buildings much more accessible, affordable, and inclusive for emerging markets and developing economies. Proptech, and the digitalisation of green building certification, have an equalising power.

Eventually, we’re able to redefine what is considered the baseline for every country, allowing everyone to elevate the standards of building design and construction.

Our work at the International Finance Corporation will continue to play a leadership role in the global transition to a low carbon path by democratising building sustainability. Central to our mandate is to encourage the greater participation of emerging markets, which are expanding at a very fast pace to keep up with high population growth and rapid urbanisation.

The real estate sector can be shaped by progressive developers that demonstrate a proof of concept and pave the way for others to follow. Along with policies and financial products that create an enabling environment for green buildings, voluntary commitments and actions by these players have been highly critical. Join us and take the challenge as we integrate proptech in green buildings, through EDGE, towards making sustainable, resilient, and affordable buildings much more accessible and inclusive for everyone.

About Angelo Tan

Angelo Tan is the Green Building Country Lead for the Philippines of the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group. In this role, he forges partnerships with real estate developers, investors, building professionals, certification providers, academia, and public policy makers across the Philippines, towards advancing the adoption of EDGE (Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies) –– an integrated online platform, green building standard, and certification system designed to make green buildings much more accessible, affordable, and inclusive for emerging markets and developing economies.

From a broader perspective, Angelo manages IFC’s green buildings program in the Philippines, creating and executing a countrywide strategic growth plan and serving as the face of the program in engaging with the community to democratize green buildings. The mission is to catalyse a virtuous cycle of supply and demand for resource-efficient buildings by setting a metrics-driven definition of what constitutes a green building, rewarding property developers for building green, increasing regulatory pull, and promoting direct investment.

Angelo has a decade of real estate experience in mixed-use development management, commercial real estate transactions, and architecture business development. He finished his Master of Sustainable Built Environment degree at UNSW Sydney and is accredited with various green building rating systems. Angelo is passionate about the nexus of sustainability and business value as manifested in how real estate firms develop and innovate amidst the time of climate change. He also believes that the ongoing discourse on sustainable design can be steered towards increasing opportunities for developing countries to participate.

The original version of this article appeared in asiarealestatesummit.com. Write to our editors at [email protected].

Recommended

Why everyone is moving to Selangor and Johor: Malaysia’s real estate comeback

Malaysia’s upturn in fortunes is especially prevalent in secondary destinations such as Selangor and Johor

Penang’s silicon boom: How the US-China tech war is supercharging local real estate

Penang’s booming semiconductor industry has created ripples within the local real estate sector

New leader, new opportunities: How Hun Manet is shaking up Cambodia’s real estate game

Hun Manet is overseeing decent economic growth and widening access to the country’s real estate market for foreigners

Singapore embraces inclusive housing reforms amid resilient demand

The Lion City’s regulatory strength continues to exert appeal for international investors