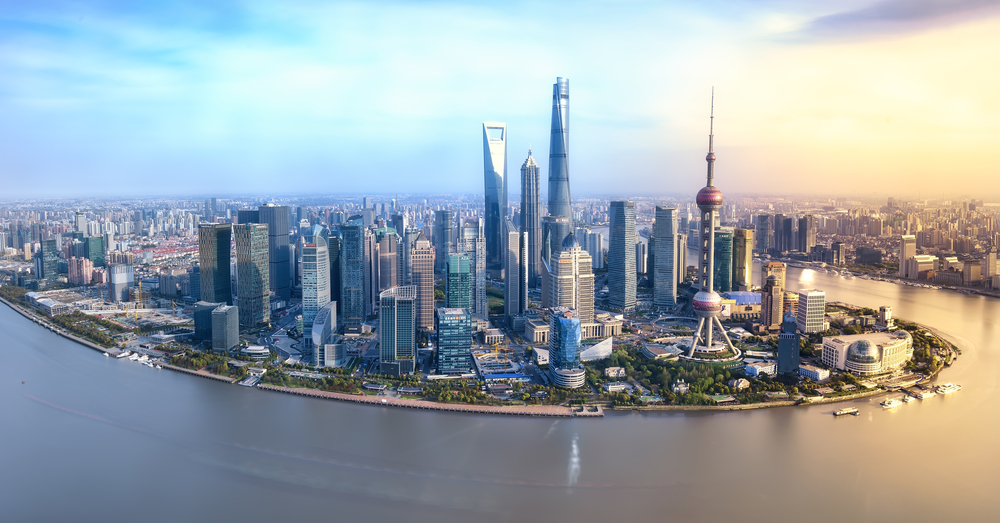

China’s housing sector makes an incredible comeback post-lockdown, but what does the future hold?

New restrictions on home loans designed to reduce exposure to China’s real estate market are yet to show signs of impact. But analysts predict the inevitable result will be a slowdown in price growth after a surge post-lockdown

The Year of the Rat in 2020 started with new house sales at a standstill as the pandemic bit hard. But by the start of the Year of the Ox in February, China’s residential market had recorded something of a property miracle.

Since lockdowns ended in cities across China in April last year, sales volumes of new homes had climbed nearly 11 percent and prices 7.5 percent compared to the previous year, according to Fitch Ratings.

On par with median rates over the past decade, home sales in China did record a minor blip. But less than a year later, the industry’s vital signs suggest the sector has developed immunity to the pandemic.

Closer inspection, though, reveals a worrying diagnosis for the central government in Beijing. In June, China’s second-largest developer by sales, Hong Kong-listed China Evergrande, reported staggering outstanding loan repayments of USD124bn—equivalent to the entire sovereign debt of Denmark.

The beleaguered firm made early bond repayments in January, easing investor and policymaker concerns after institutional state investors including SenseTime Group rallied to inject capital worth tens of billions of renminbi.

Still, the China Evergrande debacle appeared to spook Beijing, coming as it did among a host of other red flags linked to real estate. Also, in June 2020, China recorded its highest-ever household leverage ratio amid a surge in new mortgages which placed the average Chinese homeowner under a record burden of mortgage repayments.

At the end of last year, the increasingly powerful chairman of China’s Banking and Insurance Regulation Commission, Guo Shuqing, warned the rapidly recovering yet risk-laden property sector had become a dangerous “grey rhino” for the wider economy. In other words, a known threat that had thus far not been addressed.

“Among the 130 financial crises since the start of the 20th century, more than 100 of them are related to property markets,” Guo wrote in a new central government book of policy aims looking ahead to 2035.

The new guidelines will limit banks’ exposure to the real estate sector and address concerns that rising signs of overheating in the property market would weaken banking system stability

He added: “Governments won’t intervene if their risk can be solved through the market.” But weeks earlier, Chinese regulators under Guo had already begun asking property developers for more details on their debts as part of a new policy dubbed “the three red lines”: debt-to-cash, debt-to-assets and debt-to-equity.

Then the central government announced new lending restrictions, meaning large state lenders like Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the world’s biggest bank, would be required from the start of this year to cap property lending to the industry at 40 percent of total loans, and mortgages to homebuyers at 32.5 percent during a two-year transition.

Smaller banks across China’s vast countryside, where debts have accumulated under less scrutiny, now face property lending caps of just 12.5 percent and 7.5 percent.

“The new guidelines will limit banks’ exposure to the real estate sector and address authorities’ concerns that rising signs of overheating in the property market would weaken banking system stability,” says Ray Heung, senior vice-president at Moody’s China.

Guo himself has revealed the extent of the challenge facing the central government as it battles to contain property-related debt risk to the wider economy amid plans to steer China towards high-end manufacturing and greater consumption.

In November, he revealed that property-related loans account for 39 percent of all bank lending in China, significantly higher than the 28.8 percent acknowledged officially by the central bank which Guo oversees as a Communist Party chief.

The gap between the two figures points to the large chunk of loans in China funnelled into property, contravening local rules. Bank loans to help small businesses amid the pandemic have in some cases been channelled instead into dummy shell companies and used illegally for real estate investments, according to the South China Morning Post.

Large but unknown sums also reach the property sector from trusts or locally-owned investment firms which function like banks with little government oversight, the increasingly restricted peer-to-peer lending sector, and wealthy groups and families who invest capital directly with developers, says Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong and author of Shadow Banking and the Rise of Capitalism in China.

“The regulators have become tighter on examining the balance sheets of the property developers,” says Collier. “Yet, there are still ways to get around the debt limits.”

Collier correctly predicted that state firms would come to the rescue of China Evergrande, averting a property-induced financial crisis in China. He expects weaker economic conditions in China during the remainder of this year.

In the longer term, the inevitable result of government policy will be towards tighter credit, even if in the short term household loans reached record levels in January, up 26 percent to CNY944.8bn compared to a year earlier. After the Chinese New Year, there were still few signs of policy impact outside of a small increase in mortgage rates by 4 basis points, according to Rong360.com, an online loan service that tracks borrowing costs.

The new government checks and restrictions on bank loans to the property sector were not designed to rein in home price growth, says James, Savills head of China research in Shanghai.

But further policy restrictions were expected to be announced by the government this year after government delegates met in Beijing in early March for the Two Sessions political meetings which steer policy, and these would likely target surging post-lockdown property prices.

“Most (restrictions) will have the intention of curbing price growth in leading first and second-tier cities such as Shanghai and Beijing that saw strong growth in 2020 and the first month of 2021,” added James. “They will also serve to stimulate demand for lower-tier cities and to support those local markets.”

The original version of this article appeared in Issue No. 165 of PropertyGuru Property Report Magazine

Recommended

Park Kiara in Hanoi raises the bar for sustainable urban living

Park Kiara in Hanoi is a repudiation of low-density, car-dependent suburban sprawl

6 reasons Bekasi is rising as Greater Jakarta’s next hotspot

One of Greater Jakarta’s rising stars is prospering, thanks to ample recreation and a contingent of desirable housing projects

6 developments driving Asia’s green real estate shift

Developers are being incentivised to push a green agenda into daring new realms

The Philippines’ LIMA Estate drives sustainable industrial growth

LIMA Estate models a citywide vision that uplifts workers while appealing to climate-conscious employers