Balance is the new normal: Part 3. the workplace

In the third instalment, Prof. Jason considers the re-calibration of the workplace and the home office – post-pandemic

“The King is dead. Long live the King”.

So goes the obligatory proclamation made at the passing of a monarch, and the installation of an heir to the throne. Over the past few weeks, similar utterances have been mentioned about the ‘death of the workplace’. But is the office dead; and is the home office truly the rightful heir and successor?

Monarchs were created through feudal systems of acquiring land by funds or by force – manoeuvring to secure and grow territory, and presiding over the place and people by elaborate displays of power, prestige and opulence. The physical manifestations came in the form of the castles and palaces they built; each filled with more superlatives than the predecessor. Similarly, as corporations grew profitable, acquired entities and wielded greater power through market share, they also displayed symbols of power and prestige – often demonstrated in the landmark towers or sprawling campus’ geographic position within district, city or country. So whilst Covid-19 may have bludgeoned the workplace temporarily, it would be unwise to write off the King of real estate.

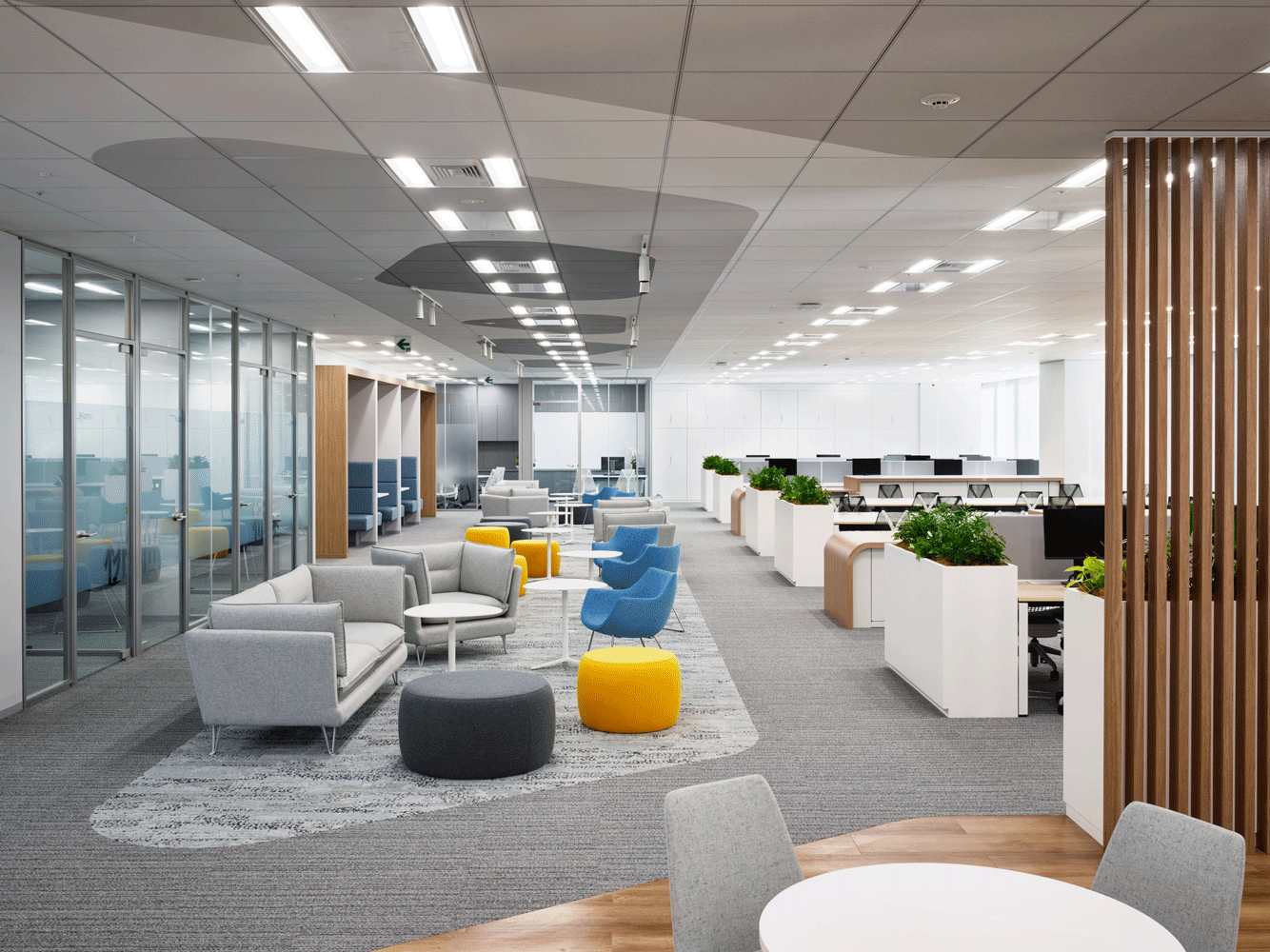

The workplace has shaped and morphed with the times and is increasingly reflecting the shift from manufacturing to digital-based economies. This shift meant that the occupancy/density/productivity conundrum, and the balance between in-situ and remote working, had started way before the pandemic. The workplace was increasingly being perceived as either a fluid ‘campus’ of egalitarian collaboration (read ‘A.N. Other Facebook’), a highly-tuned box of spatial efficiency (read ‘A.N. Other corporation’) or a repurposed space shared by strangers with good coffee and wifi (read ‘A.N. Other collaborative workspace’). All are united by a belief that being ‘smart’ (in terms of space, technology and work culture) can deliver better productivity and enhanced revenue of the corporation, group or individual. But with the pandemic, a further factor unites these models, and that is of the increasingly ‘prophylactic’ experience of the workplace.

Thermometers, hand sanitisers, QR codes, masks and occasionally even gloves serve as further lines of defence before we arrive at our work stations that have been marked with a ‘social distancing X’. The makeshift markings in tape are stark reminders that once upon a time, someone resided there. Now they have been uprooted, shifted or worst still, made redundant. Those who are in the office have extra chairs for company. These are often strewn around the empty space or, for those more organised corporations, arranged to facilitate tidy ‘crop-circles’ of conversation amongst colleagues. Hot-desking is being made possible with disposable paper desk pads on which a worker sets his or her laptop when he or she arrives, often supplemented with a further squeeze of sanitiser. Despite the sanitised experience, the office lures us back as an employee’s comfort blanket of normality and an employer’s psychological crutch of productivity.

The workplace has thrived on the paradox that presence equals productivity. Turn of the 20th-century workplaces resembled factory floors of office workers patrolled by the office manager, with the view that presence naturally delivered outputs. Whilst this view is being challenged by the pandemic predicament, the essence of surveillance as a tool to coax and cajole the worker remains; despite the shape and form of the office changing. Physical presence is still held in high esteem in some organisations. It probably comes as little surprise that in this period of remote working, some companies requested the installation of webcams in home offices to monitor presence as the prerequisite to productivity. This reminds me of an experience I had a couple of years ago as I filmed an episode of the Smart Cities 2.0 TV series, where I was tracked through an office in Songdo – an ubiquitous smart city. My presence (read productivity) was being monitored. Such technology could potentially be used to not just track the movements of workers but also act as a ‘cattle prod’ to socially distance, or proclaim the ‘unclean’ through biological data screening.

As we all know, presence in the workplace does not necessarily equal productivity. Turning up, sitting at the desk and sending emails in eye and earshot of your employer is not a measure of productivity and is rightfully being challenged. Some within my studio have found working from home more productive as it negated the need to travel, and allowed them to balance their lifestyles better. Some found themselves working longer hours as the boundaries between home and work life blurred. However, a vast majority were happy to return to the studio given the need to engage with colleagues and delineate work and home life.

It is a comment echoed by Neil Salton, Founder of workplace consultancy, ChangeWorq. “Team members may not have enough space to work effectively [from home], or simply can’t concentrate with the family being in close proximity. Others may have the space, but just prefer to be with colleagues. This is a chance to define what ‘work’ actually means. Once we know that, then we can start making decisions on what kind of space we need. What I learned from my own Work From Home (WFH) survey is that collaboration and communication are the primary reasons to be in the office, with social interaction coming a close second.

So the office is not dead, though it has been physically weakened and is finding a new path to recovery. So what can one expect when returning to the office? More space for sure. In an Architects Journal report, companies wanting employees to return to the office will have to reduce capacity on each floor by between 30-50% in respect of social distancing measures. This has led to concepts such as the ‘6 foot office’. According to Jeroen Lokerse of Cushman & Wakefield, the concept is slowly being tested at its Amsterdam office, and resembles a series of socially distancing circles that are etched into the floor as a conscientious effort of personal space awareness. It used to hold two hundred and seventy-five people but since the circuit breaker has only seventy-five at any time. As the lockdown lifts and more workers return, they anticipate having staggered start times to avoid overcrowding on public transportation, and 30% fewer desks overall.

We may be revelling in the feeling of more space right now, though arguably, this is potentially a return to how things used to be. Spatial proportions of our workstations have been shrinking for some time and becoming increasingly ergonomically attuned. We will most likely see greater personal working space which may not necessarily mean the return of chunky desks that contain half a rainforest, but a re-calibration of circulation, work station and collaboration zones. The campus-style workplace, which proffered the benefits of space to aid the health, wellbeing and productivity of the workforce, will be more of a post-pandemic reality. After all, we are still creatures that need co-presence and social interaction and the workplace will re-assert itself as a place of meeting – especially as homeworking has become, and will continue to be, an extension of the working environment (and, I hasten to add, not a replacement).

More: Rise of the digital economy and its impact on the workplace

This brings us to the consequences of accepting the very existence of the home office and its relationship to the workplace, and whether it will be an heir apparent in the future? The perceived wisdom suggests that the home office will not replace the office; rather, WFH can become part of our future working experience, suiting particular roles and personality types more than others. For instance, making an hourly commute to the office only to make back-to-back phone calls would seem nonsensical and could easily be done from home. This necessitates making informed choices of where we need to go in order to do what we need to do, and ensuring that our working environment is calibrated to optimise our productivity.

With WFH being part of the new workplace, not only will the office density have decreased noticeably, but the vibe will have changed – especially as some companies may have become enlightened to particular employees working from home, and others returning to the office. The workplace thus runs the risk of becoming polarised between ‘those who are in, and those who are out’, and the psychological effects can be potentially damaging. According to Amy Edmondson, Novartis professor of leadership and Management in Harvard Business School, “We think of ourselves as thoughtful people, and it would be silly to like someone less who’s now working at home when I’m back in the office or vice versa. But it turns out this happens with some regularity. We can’t help the sense that those who aren’t here, they’re less committed or they’re less important.”

It is thus essential for us to carefully re-calibrate the workplace not just in terms of space, but also the social and psychological well-being of the employee. Those who have childcare needs or are primary caregivers; those who are vulnerable to Covid-19, or those who have disabilities may less likely return to the office. But they should not be excluded from the conversations before the pandemic started; neither should they be disadvantaged through their lack of physical presence. This necessitates a culture of trust from the employer and the eradication of the ‘presence means productivity’ mentality. By using technology as a means of closer virtual connection, ‘out of sight’ need not mean, ‘out of mind’.

The office lives.

This is the third instalment on the series ‘Balance is the new normal.’ Read first, second, fourth, fifth and sixth parts here

About Professor Jason Pomeroy

Jason Pomeroy is an award-winning architect, academic, author and TV presenter, regarded as one of the world’s thought leaders in sustainable design. He gained bachelor and master degrees from the Canterbury School of Architecture and the University of Cambridge; and his PhD from the University of Westminster. He is the founder of Singapore-based interdisciplinary design and research firm Pomeroy Studio, and sustainable education provider, Pomeroy Academy. Pomeroy has edited Cities of Opportunities: Connecting Culture and Innovation (2020), and authored Pod Off-Grid: Explorations in Low Energy Waterborne Communities (2016), The Skycourt and Skygarden: Greening the Urban Habitat (2014) and Idea House: Future Tropical Living Today (2011). He continues to raise cultural awareness of cities through his critically acclaimed TV series ‘Smart Cities 2.0’, ‘City Time Traveller’ and ‘City Redesign’. www.jasonpomeroy.sg

About Pomeroy Academy

Pomeroy Academy are educators and researchers of sustainable built environments. The courses created and curated are specialist in nature and focus on the process of designing climate-responsive sustainable developments through an evidence-based approach. The courses seek to heighten awareness of the green agenda and provide students and professionals with the necessary skills to make a difference in their respective fields. The Academy was founded by Prof. Jason Pomeroy, whose interests lie in sharing sustainable design knowledge with an industry that is increasingly needing to respond to climate change. www.pomeroyacademy.sg

Recommended

6 developments driving Asia’s green real estate shift

Developers are being incentivised to push a green agenda into daring new realms

The Philippines’ LIMA Estate drives sustainable industrial growth

LIMA Estate models a citywide vision that uplifts workers while appealing to climate-conscious employers

Malaysia property market rebounds with foreign interest and growth

The nation’s property market is stirring to life, fuelled by foreign buyers and major infrastructure drives

China’s renewable energy surge redefines housing norms and development

From exporting solar panels to building entire green-powered neighbourhoods, China’s renewable surge is redefining housing norms